How do you feel at school? A cross-country comparative analysis of migrant adolescents’ school well-being

- Institute for Social Studies, Science and Research Centre Koper, Koper, Slovenia

Adolescents present a relevant stakeholder in international migrations since they comprise a large share of all migrants. Previous studies show that migration processes significantly affect the well-being of migrant adolescents. This article investigates how the school environment, with its pedagogical practices and interpersonal relationships established between migrant adolescents, their classmates, and teachers, affect migrant adolescents’ well-being. Our research draws on quantitative data collected as part of the MiCREATE project. The sample of migrant adolescents (N = 700) was surveyed in 46 schools in six countries: Austria, Denmark, Slovenia, Spain, Poland, and the United Kingdom. Results indicate that migrant adolescents like school and feel safe there, however, they tend to be more satisfied with relationships established with teachers than with peers. Furthermore, differences in self-perceived school well-being emerge when comparing countries with a longer tradition of high migration flows (Spain, Denmark, and the United Kingdom) and those less experienced (Poland and Slovenia), although slight exceptions were detected. The results lead to the conclusion that schools that foster intercultural education and fulfilling interpersonal relationships are essential for school well-being of migrant adolescents and present an important step toward successful integration of migrant youth.

1. Introduction

As countries around the world continue to face high numbers of migrant adolescents, various governments, international institutions, and boards have focused on the well-being of migrant youth. The latter is often presented among the key indicators (other indicators being, for example, language fluency, access to rights, academic success, sense of belonging, etc.) for evaluating how successful the integration process of migrant adolescents is. In this article, we will follow the definition of the integration process as stated by Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas (2016); it is the process by which people who are new to a country become part of the society, while it is also a process of settlement, interaction with the host society, and social change that follows migration. When using the term “migrant adolescent,” we are referring to those who are migrants themselves (also called 1st generation migrants). Considering current trends and studies, it is essential to understand the well-being of migrant adolescents, not only to ensure that they have a quality youth but also to build a solid foundation for their adult lives. The transition of migrant adolescents through the different stages of their lives will significantly affect their integration process in the host country as well as their life quality as adults. In line with this argument, well-being of migrant adolescents has become a priority in today’s multicultural, multilingual, and multireligious Europe. Political agendas reflect these trends; for example, Euro 2020 has prioritized combating poverty and social exclusion as well as improving the well-being of adolescents (Pollock et al., 2018). According to the Youth Policy Press (2014), 98% of European countries have a national government institution responsible for youth; this indicates the attention and targeted action of state institutions are in place. On the other hand, the structure and implementation of policies that address migrant adolescents and their well-being vary significantly across European countries.

Well-being of migrant adolescents (these are defined as people between 10 and 19 years old) can be severely affected by migrations through risks associated with the country of origin, during the migration, and upon arrival in the host country (World Health Organization, 2018). Plenty of migrant families are socioeconomically disadvantaged upon arrival, which results in downward social mobility after settling in the host country and this consequently increases the risk for migrant adolescents’ well-being. Migrant youth is more vulnerable also due to their specific experiences; they had to separate from social relationships established in their country of origin, may have been exposed to various forms of violence during migration, and face numerous challenges and barriers in the host country (e.g., difficulty in accessing health care, education and extra-curricular activities, experience of negative attitudes, harassment, and/or physical violence). These challenges are also reflected in the educational setting (Smith et al., 2021); while migrant adolescents learn the language of the host country and try to adapt to the educational style, they may encounter difficulties keeping up academically and socially with local peers (Wong and Schweitzer, 2017). Additionally, minorities attract prejudice and discrimination that jeopardize their overall well-being within various social settings (Säävälä, 2012; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015), for example, peer bullying. Despite evidence show that experiencing peer bullying causes negative consequences for all adolescents, regardless of their ethnicity, studies (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2010; Closson et al., 2014; Pottie et al., 2015) emphasize that migrant adolescents, marked as “outsiders,” experience higher levels of peer bullying, discrimination, and exclusion due to cultural differences. On the other hand, to combat these challenges, migrant adolescents may draw strength from the very same surrounding, as discussed in later sections of this article.

The main objective of this article is to assess the school well-being of migrant adolescents and to examine how the relationships migrant adolescents establish with teachers and peers affect their school well-being. Using the comparative approach, we aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of school well-being of migrant adolescents who live in Austria, Denmark, Slovenia, Spain, Poland, and the United Kingdom. As the below presented studies indicate, supportive relationships have been evaluated as vital for the well-being of migrant adolescents. Therefore, our research focuses primarily on the relational dimensions of school well-being. Additionally, we evalute the relationships between peer victimization, teaching practices that recognize principles of intercultural education, and self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents. The importance of intercultural education is reflected in its broad set of solutions, practices, and approaches that aim to support cultural diversity and social justice, but also in its potential to counter marginalization in education and society. In the array of approaches and methods, solutions that focus on language, customs, beliefs, traditions, literature, cultural heritage, intercultural conflicts, school management, interpersonal relationships, and similar can be identified (Portera, 2008).

First, an overview of the current theoretical debates on the topic of school well-being of migrant adolescents is presented, followed by the results of the survey, conducted in 46 educational institutions within six European countries. The sample consisted of three separate groups; newly arrived migrant adolescents (being in the host country for 2 years or less), long-term migrant adolescents (being in the host country for more than 2 years), and local adolescents. For the purposes of this article, the performed analyses focused only on migrant adolescents and their perceptions and assessments of well-being within the educational community. Finally, a discussion and implications for future research are displayed.

The findings of studies that have examined the relationship between migrant status and well-being of adolescents are contradictory. While some studies suggest that migrant adolescents are at greater risk for low well-being (see for example Shoshami et al., 2016) due to their specific circumstances, others (e.g., Alati et al., 2003) report no difference between levels of well-being among migrant and non-migrant youth. Reasons for potential lower well-being of migrant adolescents range from traumatic events that occurred prior to migration (Correa-Velez et al., 2010), the lower socio-economic status migrant families often have, the greater vulnerability and emotional distress of migrant adolescents due to migration (Pawliuk et al., 1996), and to intergenerational conflict that may arise within the family during the process of integration. Considering that migrant adolescents tend to go through the integration process faster than their parents, family conflicts and disruption may emerge. Additionally, migrant adolescents can be confronted with inadequate support from their parents, who are preoccupied with their own migration stresses (Hicks et al., 1993). Another relevant circumstance is that migrants represent a minority that differs in culture and language from the prevailing population in the host country. Consequently, migrant adolescents can encounter rejection, discrimination, and hostility that pose additional threat to the well-being of migrant adolescents. These factors could lead to the conclusion that migrant adolescents should fare relatively low on the ladder of well-being, but studies also report about the immigrant paradox phenomenon (e.g., Marks et al., 2014; Bowe, 2017). The phenomenon is often explained by the close bond that migrant parents and adolescents develop, the high aspirations and expectations migrant parents have for their offspring, consistent monitoring of their behavior, strong and extended social ties established with the migrant community, but also the ability of migrant adolescents to shift between identities, languages, and cultural norms, which may forge their resilience (Darmanaki Farahani and Bradley, 2018). Altogether, the literature thus suggests that the answer to the question which of these effects prevail is likely to depend on individual, ethnic, and contextual factors. A combination of different factors is important for resilience as well. Developmental psychologists have defined resilience as “the ability to weather adversity or to bounce back from negative experience” (Prince-Embury, 2012, p. 10). Among protective factors that contribute to the resilience are some that have roots within the family context (e.g., family warmth, emotional support, a close bond with at least one parent), however, factors associated with individual traits are also critical (e.g., intellectual ability, self-reliance, sociability, communication skills). In terms of school environment, positive school experiences, good peer relations, and positive relationships with other adults are set forth to be among the most essential. However, when discussing resilience of (migrant) adolescents, one must be aware that assessment tools for measuring this phenomenon are more prevalent for adults than for younger groups, as studies highlight (e.g., Prince-Embury, 2012; King et al., 2021).

Following increased attention paid to migrant adolescents’ well-being, scholars have recognized the fundamental role schools have in supporting migrant learners during the integration process. Furthermore, educational institutions are also important to understand the well-being of migrant adolescents. School setting has a decisive role in the lives of migrant adolescents as it can anchor them in the community, provide context to develop relationships with teachers and peers, prepare them for civic life (Weissberg and O’Brien, 2004), contribute to self-development, and set plans for the future. Schools can be especially important in providing a stable community surroundings while fostering a sense of inclusion and safety (Trentacosta et al., 2016), but more importantly, schools represent the entry point for migrant adolescents regarding establishing contact with the host country’s culture, rules, traditions, customs and similar. Similarly, the classroom environment provides a unique context in which various interactions take place; among these, intercultural exchange is significant (Wang et al., 2020).

Although research on benefits and importance of inter/multicultural education is extensive, newspapers often assess policies on multiculturalism in Europe (but also in the United States) as unsuccessful in promoting social integration. These claims are rooted in populist tendencies (e.g., growing migration, fear of Islam, economic crisis) that neglect not only various approaches but also goals of intercultural education. As Torres and Tarozzi (2019) state, such education aims at developing ethnic and cultural literacy (it expands the amount of information about the contributions of ethnic groups that traditionally had been excluded from the curriculum) and personal development (pride in one’s ethnic identity), while it also challenges attitudes, values, prejudice, stereotypes, ethnocentrism, racism and similar, promotes multicultural competence (e.g., how to understand cultural differences), and develops skills of people whose ethnic/racial background is different from the mainstream cultural capital that predominates in the curriculum. In addition, intercultural education is oriented toward achieving educational equity and excellence by developing learning methods that work across different cultures. The importance of a supportive school environment that takes into consideration various needs of migrant adolescents but also promotes the diversity they bring is clearly pronounced in studies showing that school connectedness, belonging, or membership has been associated with enhanced well-being of migrant adolescents (Chun and Mobley, 2014; Shoshami et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, schools can also hinder beneficial effects since they are recognized as settings where social inequalities and peer victimization emerge. By following the assimilationist approach and ignoring the principles of intercultural education, schools significantly jeopardize migrant adolescents’ well-being, disconnect migrant adolescents from their culture of origin and also harm their adjustment process (Bartlett et al., 2017). When, for example, educational institutions prohibit migrant learners from using their mother tongue, despite evidence that adopting the culture of the host country while retaining the original culture leads to better well-being outcomes (Fang, 2020), they prevent migrant adolescents from a successful two-way integration where both sides work toward the same goal. Several studies (e.g., Grzymała Kazłowska and Philimore, 2017; Schinkel, 2018; Medarić et al., 2021) have already rejected the perception of integration as merely passive assimilation or simple one-way adaptation to the new social reality.

In academic literature, well-being is used as an overarching concept that refers to the quality of life of people in society (Reese et al., 2010). For adolescents, well-being is determined by safe and supportive social contexts and relationships (family, school, and peers) and structural factors, e.g., socioeconomic drivers and access to education (Viner et al., 2021). Among social contexts, the classroom environment is of particular importance. The concept encompasses numerous dimensions, among which we highlight pedagogical and curriculum practices and interpersonal relationships between learners and teachers (Jones et al., 2008; Wang and Degol, 2016). Regarding the latter, socioemotional support, which expands over feeling of safety, a positive feeling of belonging, and quality interactions with teachers and peers, is recognized as a classroom characteristic that promotes well-being of learners (Danielson, 2014; Fang, 2020). Teachers create an encouraging classroom climate by responding to learners’ needs, respecting their cultural characteristics, and incorporating their opinions into learning (Quin, 2016), while peers contribute by fulfilling psychological needs of belonging (Wang et al., 2020) and feeling supported (Cuadros and Berger, 2016). Studies also suggest that a supportive peer network mitigates negative effects of migration and reinforces well-being of migrant adolescents (Smith et al., 2021). As Medarić et al. (2021: 769) state: “Schools and educators can have a critical impact and play a significant role in facilitating and supporting migrant children and youths on this journey, as they are the ones who can make a difference.”

Although there is no universally accepted definition of well-being, scholars agree that it is a multidimensional concept. According to WHO, well-being comprises an individual’s experience of their life as well as a comparison of life circumstances with social norms and values; it takes into consideration subjective and objective dimension (World Health Organization, 2012). Consequently, it is shaped and influenced by factors at the macro, mezzo, and micro levels. The scope of our article requires to focus on the characteristics and roles associated with the educational environment and thus leads us to school well-being of migrant adolescents being the focal point of the study.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

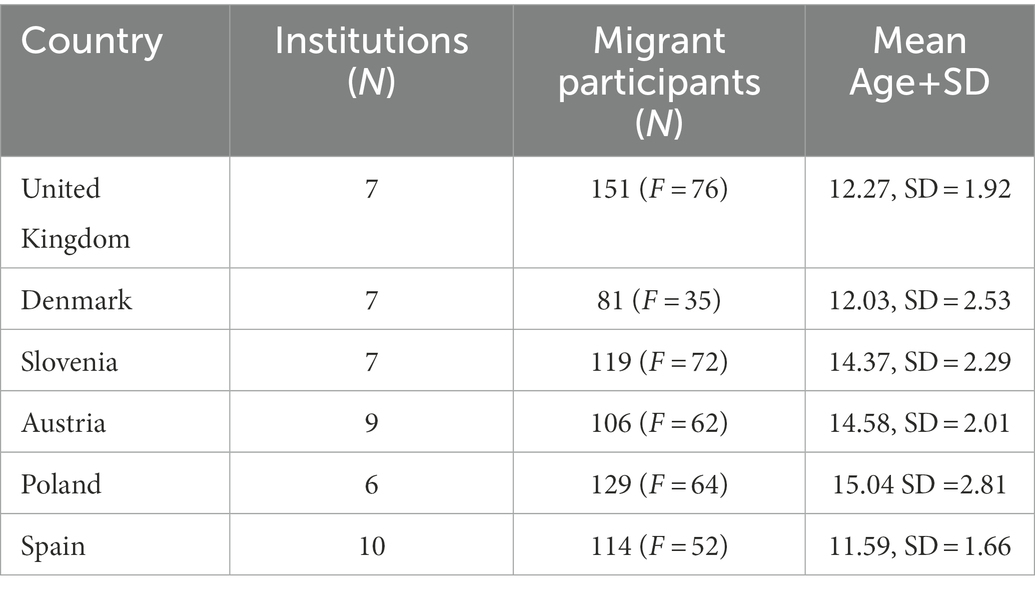

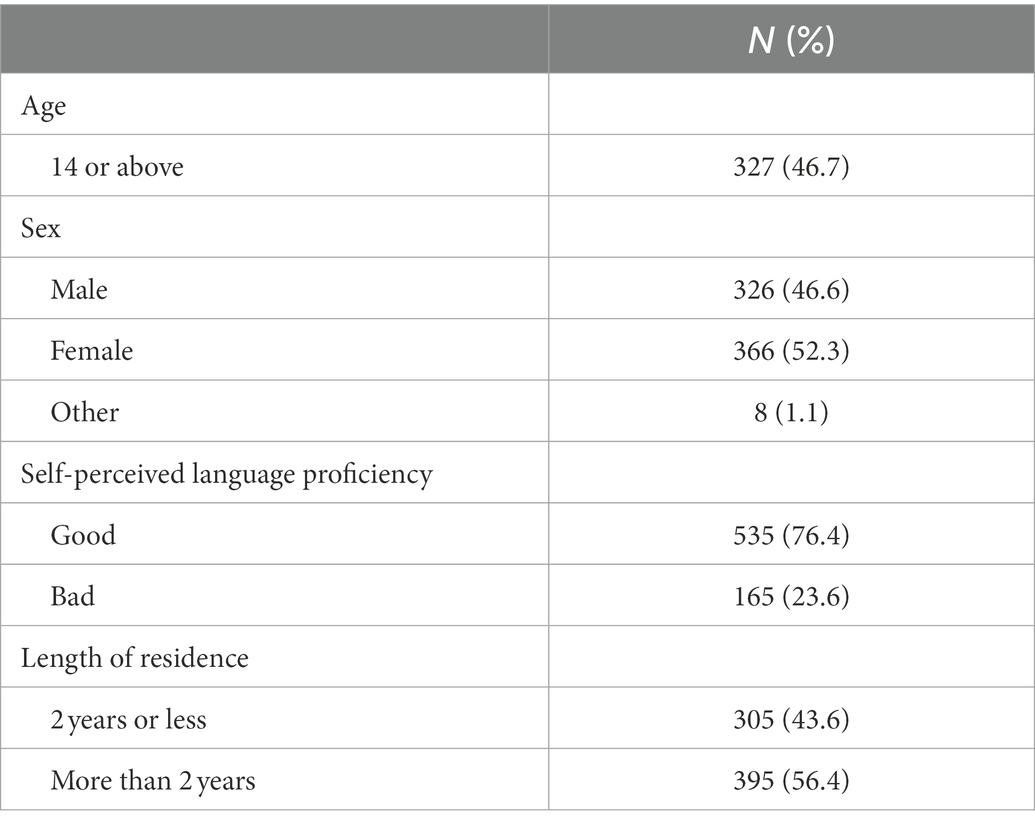

An analytical convenience sample of 700 migrant adolescents from 46 educational institutions within six countries (Austria, Denmark, Poland, Spain, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom) was included in the study (52.3% females, 46.6% males, and 1.1% identified as “other”). The sample was part of the Horizon 2020 research project MiCREATE (Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe) conducted in 2019–2022. First, districts with a high proportion of migrant population were identified. In the next phase, learners were surveyed on selected schools. As Table 1 shows, the sample in each country ranged from 6 (Poland) to 10 educational institutions (Spain). In the United Kingdom, the researchers included one online children’s and young people book club to reach a sufficient number of migrant respondents, while in Austria, a student organization had to be brought in for the same reason. For each school, a simple random selection of classes was included in the survey. Participants were divided into two age groups; age group 1 consists of learners aged 10–13 years, while age group 2 consists of learners aged 14–17 (M = 13.64, SD = 2.45). In addition, participants were divided into two groups according to their length of residence within the host country (56.4% lived in the host countries for more than 2 years).

2.2. Procedure

After gaining ethics clearance from the school, learners (and their parents or legal guardians) signed the consent form before completing the questionnaire. The instruments were translated into 13 languages (Albanian, Arabic, Bosnian, Catalan, Danish, English, German, Macedonian, Polish, Russian, Slovene, Spanish, and Ukrainian), with a back translation carried out by a professional translator to ensure the equivalence of meaning. As results revealed later, 76.4% of migrant adolescents evaluated their language proficiency in host country’s language as good; however, with the decision to have a questionnaire in different languages, researchers aimed at migrant adolescents with weaker levels of proficiency. The questionnaire was tested by the Child Advisory Board in each country and adapted accordingly. Measurement scales were based on good reliability and validity (α > 0.85). Participants were asked to complete the survey in a classroom or similar place in the presence of the researcher and/or the teacher, using their smartphones or computers. During the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, the survey was administered online in the form of a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI). All phases of the research were conducted in accordance with international and national ethical standards. All analyzes were computed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27).

2.3. Measures

The survey was based on items from previous questionnaires on child and adolescents’ well-being from a child-centered perspective, such as the European Cohort Development Project (2018), Children’s Worlds Survey (2013), and The Children’s Society (2010). Analyzes include surveys that were completed, as well as those that had at least 75% of questions answered.

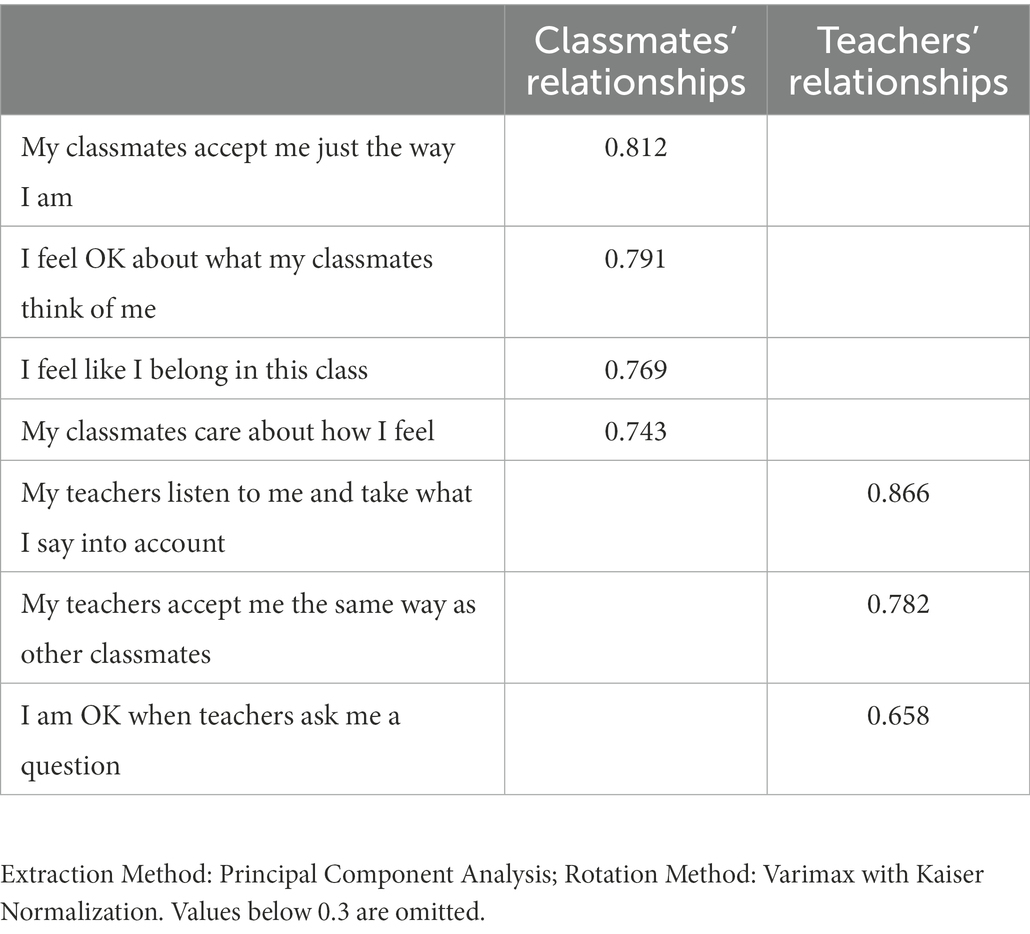

The 7-item well-being scale was used as a multidimensional instrument to assess the school well-being of migrant youth within the educational community. As Table 2 shows, the scale includes the following items: I feel OK about what my classmates think of me, My classmates accept me just the way I am, I feel like I belong in this class, My classmates care about how I feel and My teachers listen to me and take what I say into account, My teachers accept me the same way as other classmates, I am OK when teachers ask me a question. Response options were given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from Never (1) to Always (5). We conducted an exploratory factory analysis. A principal component analysis was performed on these items, followed by varimax rotation that resulted in two dimensions: relationships with classmates and relationships with teachers. As all items had a factor loading >0.3, they were retained in this study, while a two-factor solution accounted for 65% of the total variance. The scale had a good reliability score (Cronbach’s alpha >0.83). All dimensions proved to be stable and composed by the same items in all six national samples.

In contrast to some other studies (e.g., Lee et al., 2012; Fang, 2020), we decided not to control for the socioeconomic status of migrant families, as longitudinal studies (e.g., Ozan et al., 2018) show that this association is not as strong for adolescents as it is for adults. Similarly, we decided not to control for academic success. As Jonathan Bradshaw (2009), one of the leading researchers in the field of cross-country comparisons of child well-being, notes, there is no consensus on whether this is a relevant indicator of adolescent well-being. In his words “Education attainment may be an indicator of well-becoming, but it is not a good representation of well-being.” (Bradshaw, 2009: 8).

In addition, we analyzed two additional indicators of school well-being that were excluded from the factor analysis but have solid theoretical relevance regarding migrant adolescents’ well-being. These include perceived feeling of safety (I feel safe when I am at school) and school satisfaction (I like being in school). Both questions had answers given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from Never (1) to Always (5). These two indicators were single-item measures. The convergent validity of both indicators was tested separately and prior to the pilot. Both items were correlated with their multi-item counterpart (r = 0.70) of the previously mentioned questionnaires.

At this point, it should be highlighted that disadvantages of single-item measures (e.g., lower reliability, vulnerability to measurement error, inadequate depiction of complex experience) were taken into consideration during the preparation of the questionnaire. Due to several important characteristics of our respondents, for example their belonging to vulnerable population, short attention span, their cognitive and emotional resources, the decision to make a questionnaire as time sensitive as possible was made. Consequently, these items can appear as too generic. During the pilot phase and surveying in researchers’ presence, there were no comments, questions or suggestions related to these two questions. When asking about feeling safe at school, the objective was to collect data on the number of migrant adolescents who perceive school as a positive space where they are not subject to physical or psychological discomfort. Regarding school satisfaction, the question focused on learning, social activities and opportunities that take place in school.

Considering the needs of migrant adolescents, we analyzed three items related to language use within the school environment. The first question was Are children allowed to speak other languages in your school (e.g., in the hallways, when playing, etc.), followed by During classes, do teachers sometimes speak with children in other languages or ask learners how something is said in other languages? and My teachers talk about different countries, languages, religions and culture. We created a dichotomous variable where 0 presents experiencing such practice (yes) and 1 presents absence of it (no).

Following studies that discuss the impact of peer victimization on learners’ school well-being, we used three items that took into account migrant adolescents’ experiences during the past school year (How often did children make fun of you, call you unkind names, spread lies about you, share embarrassing information about you or threaten you?/How often did they hit or hurt you?/How often did they leave you out of their games or activities?). The answers were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from Never (1) to More than three times (4). We created a new dichotomous variable labeled as peer victimization where 0 indicates that unfavorable peer behavior was experienced and 1 marks the absence of it.

3. Results

First, analysis of the demographic variables were carried out and are presented in the Table 3.

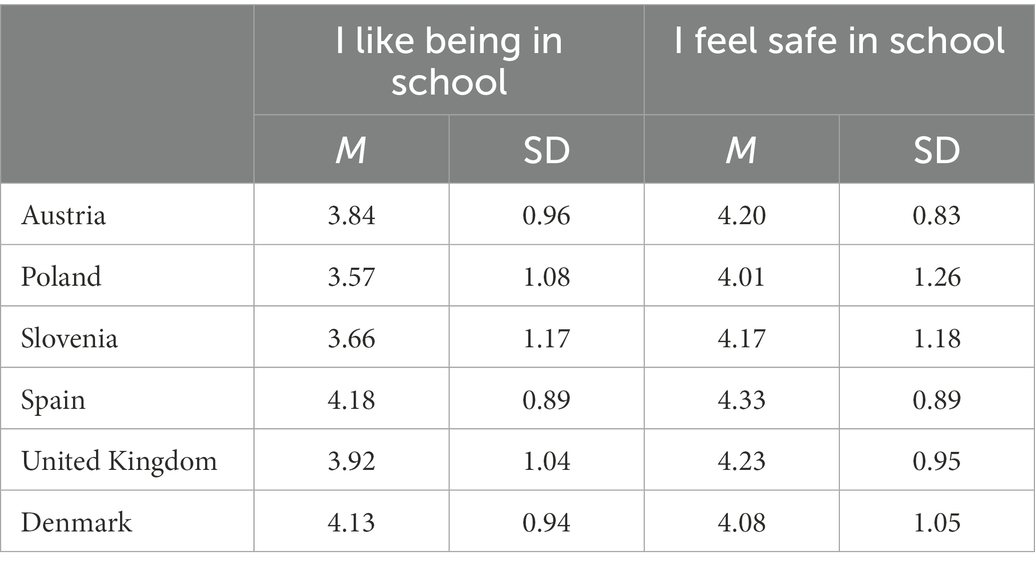

The results are presented in three sections. Firstly, we analyzed mean group differences on more general and straight-forward indicators of school well-being known as school satisfaction and perceived feeling of being safe in school (the results are shown in Table 4). In the next step, we analyzed group differences on relational indicators of school well-being (relationships between migrant adolescents and their classmates and between migrant adolescents and their teachers). Finally, we examined the correlational link between school well-being and peer victimization. Additionally, we were interested in specific teaching/curriculum practices related to cultural diversity and migrant adolescents’ well-being.

When migrant adolescents were asked whether they like being in school, we found that the average satisfaction was rather high (M = 3.86, SD = 1.04). The highest scores were obtained from migrant adolescents attending schools in Spain (M = 4.18, SD = 0.89), closely followed by Denmark (M = 4.13, SD = 0.94) and the United Kingdom (M = 3.92, SD = 1.04), while the lowest scores were observed in two post-socialist countries, Slovenia (M = 3.66, SD = 1.17), and Poland (M = 3.57, SD = 1.08).

Another dimension relevant to school well-being is the perceived feeling of safety. This item spotlights sense of migrant adolescents feeling nothing harmful and/or discomfortable will occur to them while being in school. In all six countries, migrant adolescents reported high values of feeling safe (M = 4.17, SD = 1.04); comparing this to the results from the other column, migrant adolescents might not experience school as utterly pleasant place, neverthless, it is still a safe haven for many of them. Again, these scores were above the average value for migrant adolescents attending schools in Spain (M = 4.33, SD = 0.89) and the United Kingdom (M = 4.23, SD = 0.95), while Austria (M = 4.20, SD = 0.83) performed better in this indicator comparing it with previous one. The lowest result was obtained in Denmark (M = 4.08, SD = 1.05), a country with high migration flows, and Poland (M = 4.01, SD = 1.26).

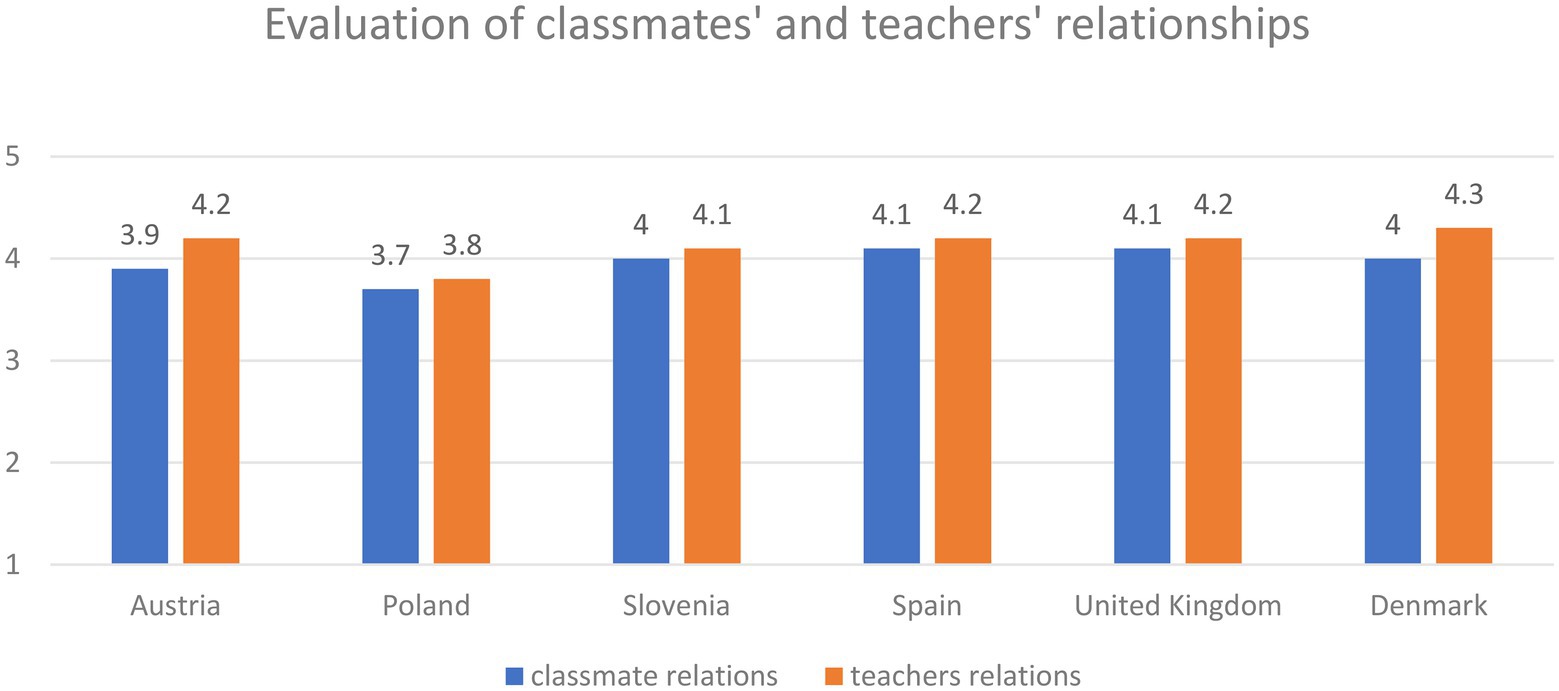

Following the theory and our factory model, we analyzed school well-being through the relationships migrant learners develop with their classmates and teachers. Our results presented in the Figure 1 indicate that migrant adolescents are most satisfied with classmate relationships in Spain (M = 4.11, SD = 0.66) and the United Kingdom (M = 4.11, SD = 0.75). In no country were the relationships evaluated as particularly unfavorable; however, both indicators were the lowest in Poland (M = 3.71, SD = 0.98) compared to other countries.

When evaluating the relationship between migrant adolescents and teachers, migrant youth from Denmark (M = 4.3, SD = 0.77) perceive these relationships to be the most satisfying, while migrant adolescents from Poland are the least satisfied (M = 3.8, SD = 0.85). Moreover, the results reveal that in all six countries, migrant youth rank their relationship with teachers higher than they assess their relationship with classmates.

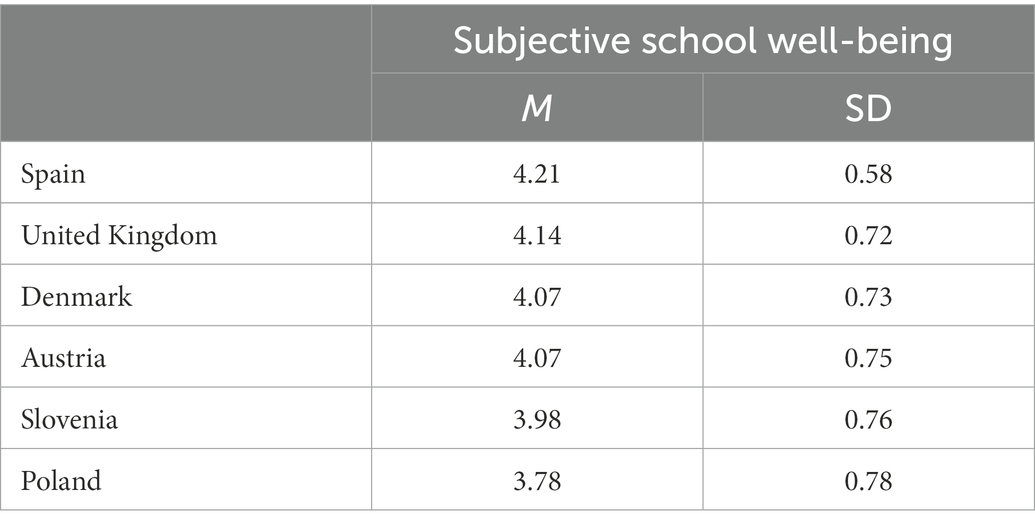

In the next step, we combined both relational dimensions into a construct and labeled it as self-perceived school well-being (as Table 5 shows). Overall, migrant adolescents evaluated their subjective school well-being the highest in Spain (M = 4.21, SD = 0.58) and in the United Kingdom (M = 4.14, SD = 0.72), while subjective school well-being was slightly lower in Slovenia (M = 3.98, SD = 0.76) and Poland (M = 3.78, SD = 0.78). Correspondingly to school likeability, the lowest levels of self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents were obtained in both post-socialist countries. In the following table, the mean values are arranged in a descending order.

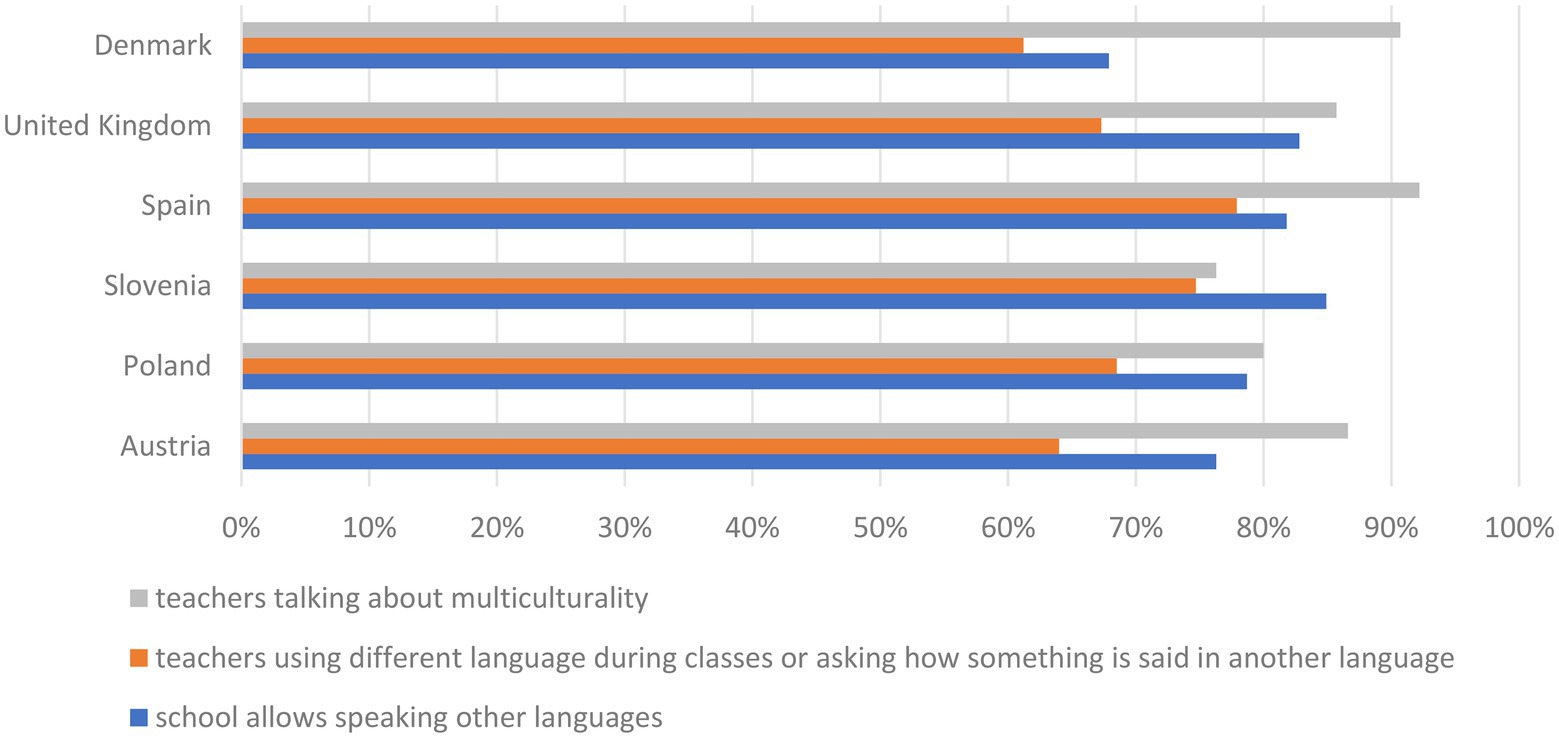

Figure 2 examines two methods of intercultural education that focus on language use. The ability to use their mother tongue even after settling in the host country is, as studies report, of immense importance for migrant adolescents. The results below suggest that in all countries, at least to some extent, school advocates for the policy of allowing migrant learners to speak different languages in hallways, playground, school cafeteria, and similar places. However, fieldwork experience confirms that in all countries, language of the host country was more approved than other languages. The practice of encouraging the use of various languages in school premises was the least common in Denmark; 67.9% of migrant adolescents confirmed that such behavior was allowed. On the other hand, in Slovenia, it was most widespread, resulting in 84.9% of migrant learners confirming that different languages can be spoken at school.

Inside classrooms, teachers in different countries respond differently to acknowledging multiculturalism (e.g., speaking about different cultural practices, traditions and habits, religious and racial groups) and using different languages or asking migrant learners how something is said in their mother tongue. For example, compared to teachers from Spain (78%) and Slovenia (76.3%), it is particularly striking how rarely (migrant) adolescents in the United Kingdom (67.3%) and Denmark (61.2%) hear teachers using different language than the mainstream inside the classroom. Similarly, it is less common for teachers in Denmark, Austria, and the United Kingdom, compared to their colleagues in other countries, to ask migrant adolescents how something is said in their language.

Furthermore, according to migrant adolescents, teachers are particularly likely to talk about multiculturalism in Spain (92.2%) and Denmark (90.7%). In the questionnaire, this item was interested in teachers speaking about different languages, cultures, religions, and countries in a positive manner during classes. The results were also promising in Austria (86.6%) and the United Kingdom (85.7%), while Slovenia obtained the lowest result (76.3%).

Observing all three indicators together, the results show that migrant adolescents in Spain rank the frequency of these indicators the highest.

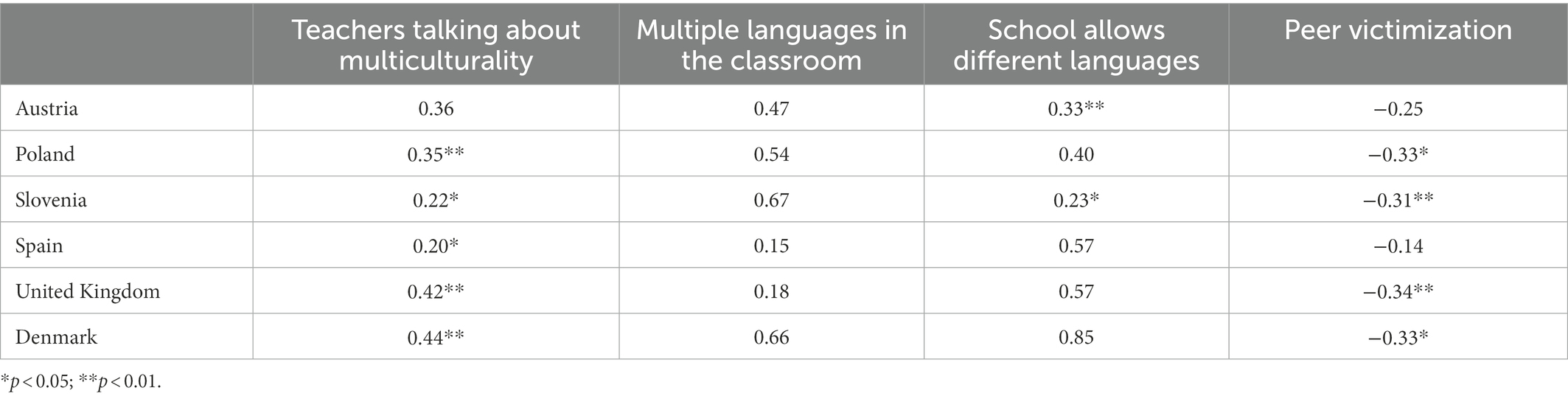

The items related to teaching and curriculum practices that acknowledge cultural diversity in schools, as well as peer relationships measured as peer victimization, were analyzed using Spearman’s correlations (Table 6). Each of the four variables presented below has been correlated with the composite variable labeled as school well-being. When looking at the correlations between school well-being and teachers discussing multiculturality in classes, there were correlations related to teachers talking about different cultures, languages, countries, religions, etc. during classes. The only exception was Austria where the results were not statistically significant. A correlation was present also with the school leading the policy of allowing different languages in the hallways, school cafeteria, playground, and similar facilities [the correlation was significant only in Austria (rho = 0.33) and Slovenia (rho = 0.23)]. In no country was there a statistically significant correlation for the use of different languages or asking how something is said in another language.

Table 6. Correlation statistics between school well-being and teaching practices/peer victimization.

Considering that migrant adolescents are more likely to be subject of peer victimization, we were also interested in investigating this correlation. As expected, the correlation was negative in all countries. Therefore, this study confirms that experience of peer victimization negatively affects the school well-being of migrant adolescents.

4. Discussion

In light of the comparative potential of countries that differ significantly in their historic experience with migration and integration, and were not, to our knowledge, prior analyzed together along the dimensions presented in the paper, the aim of this cross-country study was to investigate the experiences and perceptions of migrant adolescents regarding their self-perceived school well-being. Moreover, the influence school setting in Austria, Denmark, Slovenia, Spain, Poland, and the United Kingdom has on migrant learners’ school well-being was another point of interest. During analyzes, we focused on general but also more specific indicators of self-perceived school well-being (e.g., school satisfaction and feeling of being safe), while also considering the role of interpersonal relationships and methods of intercultural education on the school well-being of migrant learners.

Self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents is, to a certain extent, reinforced by teaching and curricular practices that recognize cultural diversity in schools, while peer bullying poses a threat. Within the next lines, we will examine this statement more thoroughly. A central information that should be highlighted is that many migrant adolescents in all six countries, regardless of differences on micro (individual), mezzo (school), and macro (country) level, like school and feel safe there, which is an important step toward high levels of school well-being. Although expectations were that countries with longer tradition of high migration flows (e.g., the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Spain) will overall perform better than post-socialist countries (Poland and Slovenia) due to their vast experiences with integration, the results were not entirely in line with this assumption.

For example, in the case of Denmark, teachers were less in favor of acknowledging different languages that are spoken within school facilities compared to other countries. Intercultural teaching practices of school professionals in Denmark seem to be affected by the insecure life situations of refugee and migrant adolescents. When teachers perceive migrant learners as temporarily present, they question practicality of adapting the teaching process to them. The link between lower levels of migrant learners’ school well-being when the use of mother tongue is restricted was previously confirmed in the study by Fang (2020). Another important factor that shapes teaching decisions in Denmark are policies that enable racialization inside the school’s walls (Hellesdatter Jacobsen and Piekut, 2022). These policies go hand in hand with increasingly restrictive policies regarding migration and integration in Denmark (see for example Rytter, 2019) that operate like fuel for conflicts, polarization, discrimination, and nationalist discourse not only outside but also inside schools. These circumstances reflected in our study as well; Denmark (together with Poland) was recognized as a country where migrant adolescents identify school as less safe as their peers in other countries. Feelings of safety are undoubtedly associated with self-perceived school well-being – our results show that migrant adolescents who like school also feel safe there and vice versa. Considering findings about school satisfaction and safety, a sense of connectedness to school should be, for example, fostered through mentoring interventions.

On the contrary, Slovenia, a post-socialist country, obtained high results regarding indicators associated with methods of intercultural education (especially school language policy) despite its limited experience with (school) integration of migrant adolescents. This lack of experience is often expressed by inadequate and inappropriate educational approaches that were criticized in other studies (see for example Rutar, 2018; Dežan and Sedmak 2020; Medarić et al., 2021; Vižintin and Kern, 2022). These authors concluded that primary and secondary schools in Slovenia still have a long way to implement intercultural dialogue in pedagogical activities thoroughly, however, our findings signalize turn for the better.

Albeit intercultural education has been widely accepted as a principle and a response to cultural diversity in Europe and an important strategy for the successful integration of migrant learners, our findings show that the prevalence of intercultural practices varies widely across the six countries. The results thus revealed that “teachers talking about multiculturality” was the most frequently present intercultural educational practices (Slovenia being an exception there as shown above); more than 80% of migrant adolescents rated this practice as sometimes or often present. As Machovcová (2017) points out, schools that acknowledge and support migrant adolescents’ original culture can anticipate benefits for their well-being and integration. While we recognize that implementing the principle of intercultural education is challenging because it requires systemic change and a shift in the perspective of pedagogical staff, results indicate how valuable it is for migrant adolescents’ school well-being when educational institutions acknowledge variety of cultures that co-exist there.

Furthermore, this study showed that migrant adolescents are, in general, more satisfied with the relationships they have established with teachers than with their classmates. Internal differences (when assessing peers’ and teachers’ relationships) as well as differences across countries were not vast, but migrant adolescents evaluated relationships with school staff as somewhat more favorable in comparison with relationships they develop with their peers. Following Samdal et al. (1998) highlighting that teachers’ influence is more important for school satisfaction than peer influence, our results could be a favorable future circumstance for the integration of migrant adolescents. Generally, as Danielson (2014) pointed out, socioemotional support promotes high levels of school well-being, but evaluation of relationships from our study suggests that we can indirectly assume that teachers, partly due to their professional duty, act more acceptingly toward migrant adolescents than their peers. However, studies (e.g., Kaukko et al., 2022) reveal differences among migrant learners in reaching out to teachers at the level of time spent in the host country; migrant learners who had been in the host country for <1 year less frequently requested help and support from school professional in comparison to migrant adolescents who had been there for a longer period. Although time dimension was not part of our analyzes, it should be taken into consideration.

Similar observations in terms of migrant adolescents and their engagement in relationships with peers was found also in studies of Iranian refugee youth in Turkish schools (Şeker and Sirkeci, 2015) and migrant learners in Finnish schools (Kaukko et al., 2022). Among decisive factors that challenge peer relations and contribute to peer rejection were cultural differences, negative attitudes local learners (and their families) have considering migration and integration, and low self-esteem of migrant adolescents that stems from limited language skills (Şeker and Sirkeci, 2015). Once more, it was confirmed that language barrier prevents migrant learners from making friends with new peers. Note that this limitation extends over several other domains, for example, academic performance since language fluency affect migrant learners’ academic success, thus making migrant youth even less appealing in peer’s eyes. Considering the correlation between peer victimization and school well-being of migrant adolescents, a negative association is no surprise. Migrant adolescents are at higher risk associated with peer bullying due to their cultural characteristics (Closson et al., 2014; Pottie et al., 2015). This correlation was the strongest in the analyzes performed. More importantly, this result highlights an area of the school environment that needs to be thoroughly addressed to ensure adequate development of migrant adolescents’ well-being. Policies and practices that establish safe communities and schools (e.g., anti-bullying and anti-discrimination programs) can help to tackle this issue.

Overall, the results of the various analyses imply that Spain, a country with long tradition of migrations, still performed best among all six countries. This goes in line with results from the comparative study by Rojas et al. (2021), where Spain stands out in terms of the establishment of several necessary and positive measurements related to integration policies within the school setting (for example, developing teaching practices that incorporate interculturality and tackling issues of segregation and lower academic achievements of migrant learners) Reasons for general lower results in Poland, but also Slovenia, may be found in the explanation that, until recently, both countries were perceived as homogenous in terms of population. Significant changes in terms of migrant flows and characteristics of migrant population appeared in past years, however, these changes are not reflected in sufficient state-supported integration programs delivering, for example, additional language classes and integration activities between migrant and local population but also trainings for teachers. Consequently, school professionals in Slovenian and Polish schools might have less sufficient knowledge, tools, and experience regarding migrant learners’ integration in comparison to their colleagues from Austria, Denmark, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Moreover, Slovenia and Poland face similar structural problem; without typical migration districts in cities and following the procedure of enrolling migrant adolescents into schools located in the area of their domicile, migrant learners are dispersed between numerous schools as Kościółek (2020) points out. Consequently, they do not build visible community and the integration is dependent on the teacher’s sensitivity and ability. On the other hand, Poland and Slovenia experienced migration flows from surrounding countries after the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia collapsed in 1991/1992. Following these events, plenty of people gained their hands-on experience with migration and integration of people (with similar cultural background) while being classmates of these migrants and refugees. It is possible that 30 years later, they translated these experiences into their teaching practice.

Above mentioned domains relate to the focal point of our article, the self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents, and it is reassuring to see that its levels were high in all countries. Our study indicates that migrant adolescents perform relatively well in terms of this indicator despite growing up, socializing, and educating in different circumstances that extend from micro to mezzo and macro level. However, additional efforts must be made in the process. The school environment, and especially the classroom environment, is not only an important academic learning setting, but serves as a developmental context (Wang et al., 2020) and a pillar for the successful inclusion of migrant adolescents. We have highlighted the importance of establishing supportive relationships, as they appear to be important for migrant adolescents’ well-being, but also pay attention to the recognition of cultural diversity within the school community. Migrant adolescents (as well as other members of the school community) are a vital source of knowledge regarding how to address school well-being and overcome potential barriers. At a time when countries in Europe face the challenges of integrating large numbers of migrant adolescents, national governments and societies would benefit from including migrant adolescents (as well as school staff and family members) in systemic deliberation on tackling integration and preventing inequalities. Educational environment promotes social equity and equal opportunities for migrant adolescents, however, current, and past findings (see for example Machovcová, 2017; Gornik et al., 2020; Kościółek, 2020; Medarić et al., 2021) have demonstrated that educational systems need to ensure that any specific needs that impact migrant adolescents’ well-being should be identified and targeted. Providing adequate support for migrant adolescents through available resources is an essential step in helping this increasingly growing group of youth to cope with the challenges that integration brings along.

5. Conclusion

Although the relationship between educational environment and school well-being has been extensively studied, fewer studies have addressed the specific relationship between school well-being and migrant status. Moreover, to our knowledge, no study has previously considered comparing this specific set of countries to assess the self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents. We aimed to examine how is self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents affected by the relationships migrant adolescents develop with teachers and classmates and how intercultural education contributes to school well-being of migrant adolescents.

Our findings are consistent with evidence on teacher and peer support for adequate well-being development for migrant adolescents within educational institutions (see for example Quin, 2016; Pollock et al., 2018; Fang, 2020; Smith et al., 2021). Similarly, peer victimization has been identified as a risk factor for school well-being of migrant adolescents. A novel contribution of our study lies in fact that to some extent, countries that are more experienced in migration and integration processes truly perform better (especially Spain), but this does not mean that we could dismiss other countries with less experience. It is likely that the willingness and internal motivation of teachers for integration as well as experience of school staff to recognize and adopt the methods of intercultural education are decisive factors. The importance of addressing multiculturalism in the classroom has also been highlighted in other studies (e.g., Machovcová, 2017; Wang et al., 2020; Medarić et al., 2021; Rojas et al., 2021).

In terms of strength of this article, the comparative nature of the study allowed us to examine the perspectives and experiences of migrant adolescents in different European countries. These countries share several characteristics, but, on the other hand, they are recognized by their different approaches to migration and integration of migrant adolescents. Considering these similarities and differences, we were able to conclude that the self-perceived school well-being of migrant adolescents is not as dependent on macro factors (country migration flows and its experience with migration and integration) but it is rather a compendium of factors extending over micro, mezzo, and macro level. Countries that have only recently faced integration and migration challenges can be similarly successful as countries with historically high migration flows, if they are attentive that educational institutions, also recognized as the entry point for migrant adolescents where they encounter the host country’s culture, works in adolescents’ best interest. This means that governments and schools must strive to create a safe, supportive, inclusive, and respectful environment. At the time of finalizing this article, schools are experiencing yet another increase in the number of migrant (and refugee) learners. The war in Ukraine has brought migrant adolescents to primary and secondary schools in Europe, and their background as well as educational histories differ from migrant adolescents that came, for example, in 2015. The findings of our study suggest that although schools need more resources and support from the state and local community, the foundations for high levels of school well-being of migrant adolescents are strong.

Nevertheless, our findings should be considered in light of a number of limitations, which we discuss in more detail in the following lines. These also serve as gaps that should be addressed in future research. Among significant limitations, we can highlight that these results are largely based on mean values and correlational studies, therefore, we cannot assume causality in the relationship between school environment and migrant adolescents’ well-being. The cross-sectional study design presents another limitation since it hinders the ability to test the developmental trajectories of migration effects on the well-being of migrant adolescents. Despite a strong theoretical basis for classroom environment as an antecedent for school well-being, there is a need for longitudinal studies that will address these relationships more thoroughly. Moreover, using a one-item measure for school satisfaction and perceived safety reduces this paper’s ability to depict experience of migrant youth accurately. In addition, we used only self-reports in investigating migrant adolescents’ outcomes. The use of self-reports is one of the most applied methods in obtaining information on subjective well-being; however, self-reports are susceptible to several sources of bias. Additionally, attention must be paid to social desirability effects. Another issue that must be considered when reading this data and findings is temporality. A considerable amount of data was obtained during one of the largest health crises and this certainly impacted thoughts of at least part of the respondents who participated in this research. After numerous negotiations with schools, data collection often involved many challenges and alterations to study methods. Furthermore, one of the most challenging aspects of conducting surveys was the limited time school personnel could provide to facilitate the research. Lastly, the lack of scholarly consensus regarding school well-being requires a caveat. Our conceptualization of school well-being did not exhaustively and holistically capture the multitude of indicators.

Future studies should investigate how individual and contextual characteristics moderate the relationship between the school/classroom environment and migrant adolescents’ school well-being. Considering multiple perspectives of the school environment and multiple indicators of school well-being will contribute to a more nuanced picture of which school factors are related to which indicators of well-being. Following these steps, prevention and intervention strategies could be developed and implemented.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Science and Research Centre Koper Ethics Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LD and MS contributed to conception and design of the study. LD organized the database, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, wrote introduction, methodology, results, and first draft of discussion and conclusion. MS wrote sections of the discussion and conclusion. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The article is published with a financial support of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement no. 822664 and Slovenian Research Agency program “Liminal Spaces: Areas of Cultural and Societal Cohabitation in the Age of Risk and Vulnerability” (no. P6-0279).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articless/10.3389/feduc.2023.1003762/full#supplementary-material

References

Alati, R., Najman, J. M., Shuttlewood, G. J., Williams, G. M., and Bor, W. (2003). Changes in mental health status among children of migrants to Australia: a longitudinal study. Sociol Health Illness 25, 866–888. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00373.x

Bartlett, L., Mendenhall, M., and Ghaffar-Kucher, A. (2017). Culture in acculturation: refugee youth’s schooling experiences in international schools in new York City. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 60, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.005

Bowe, A. G. (2017). The immigrant paradox on internalizing symptoms among immigrant adolescents. J. Adolesc. 55:1. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.01.002

Bradshaw, J. (2009). Child well-being in comparative perspective. Child. Aust. 34:1. doi: 10.1017/S1035077200000481

Children’s Worlds Survey (2013). Available at: https://isciweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Session1-ChildrensWorlds.pdf (Accessed June 20, 2022).

Chun, H., and Mobley, M. (2014). The 'immigrant paradox' phenomenon: assessing problem behaviors and risk factors among immigrant and native adolescents. J. Prim. Prev. 35, 339–356. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0359-y

Closson, L. M., Darwich, L., Hymel, S., and Waterhouse, T. (2014). Ethnic discrimination among recent immigrant adolescents: variations as a function ethnicity and school context. J. Res. Adolesc. 24:4. doi: 10.1111/jora.12089

Correa-Velez, I., Giffor, S. M., and Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: social inclusion and well-being among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Sci. Med. 71:8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

Cuadros, O., and Berger, C. (2016). The protective role of friendship quality on the well-being of adolescents victimized by peers. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 1877–1888. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0504-4

Danielson, C. (2014). The framework for teaching evaluation instrument. Princeton, NJ: The Danielson Group. Available at: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/17302/2013_FfTEvalInstrument_Web_v1.2_20140825_.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 20 June, 2022).

Darmanaki Farahani, L., and Bradley, G. L. (2018). The role of psychosocial resources in the adjustment of migrant adolescents. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 12:3. doi: 10.1017/prp.2017.21

Dežan, L., and Sedmak, M. (2020). Policy and practice: the integration of (newly arrived) migrant children in slovenian schools. Annales: Seria historia et sociologia 30:4. doi: 10.19233/ASHS.2020.37

European Cohort Development Project (2018). Available at: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/777449 (Accessed 18 June, 2022).

Fang, L. (2020). Acculturation and academic achievement of rural to urban migrant youth: the role of school satisfaction and family closeness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.11.006

Gornik, B., Dežan, L., Sedmak, M., and Medarić, Z. (2020). Distance learning in the time of Covid-19 pandemic and the reproduction of social inequality in the case of migrant children. Družboslovne razprave 36, 94–95.

Grzymała Kazłowska, A., and Philimore, J. (2017). Introduction: rethinking integration. New perspectives on adaptation and settlement in the era of super-diversity. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44:2. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341706

Hellesdatter Jacobsen, G., and Piekut, A. (2022). Integrating' immigrant children? School professionals' reflections on the boundaries between educational ideals and society’s problematization of immigrants. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 22:2. doi: 10.1111/sena.12369

Hicks, R., Lalonde, R. N., and Pepler, D. (1993). Psychosocial considerations in the mental health of immigrant and refugee children. Can. J. Commun. Ment. Health 12:2. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1993-0019

Jones, S. M., Brown, L. J., and Aber, J. L. (2008). “Classroom settings as targets of intervention and research” in Toward positive youth development: Transforming schools and community programs. eds. M. Shinn and H. Yoshikawa (New York: Oxford University Press), 58–79.

Kaukko, M., Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., and Haswell, N. (2022). Migrant-background student experiences of facing and overcoming difficulties in Finnish comprehensive schools. Educ. Sci. 12:7. doi: 10.3390/educsci12070450

King, L., Jolicoeur-Martineau, A., Laplante, D. P., Szekely, E., Levitan, R., and Wazana, A. (2021). Measuring resilience in children: a review of recent literature and recommendations for future research. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34:1. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000663

Kościółek, J. (2020). Children with migration backgrounds in polish schools – problems and challenges. Ann. Istrian Mediterranean Stud. Ser. Historia et Sociologia. 30:4. doi: 10.19233/ASHS.2020.40

Lee, Y. M., Shin, O. J., and Lim, M. H. (2012). The psychological problems of north Korean adolescent refugees living in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 9:3. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.3.217

Machovcová, K. (2017). Czech elementary school teachers’ implicit expectations from migrant children. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 53, 92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.12.006

Marks, A. K., Ejesi, K., and Coll, C. G. (2014). Understanding the U.S. immigrant paradox in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. Perspect. 8:2. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12071

Medarić, Z., Sedmak, M., Dežan, L., and Gornik, B. (2021). Integration of migrant children in Slovenian schools. Cult. Educ. 33:4. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2021.1973222

Ozan, J., Mierina, I., and Koroleva, I. (2018). “A comparative expert survey on measuring and enhancing children and young People’s well-being in Europe” in Measuring youth well-being: how a pan-European longitudinal survey can improve policy. eds. G. Pollock, J. Ozan, H. Goswami, G. Rees, and A. Stasulane (Springer International Publishing), 35–55.

Pawliuk, N., Grizenko, N., Chan-Yip, A., Gantous, P., Mathew, J., and Nguyen, D. (1996). Acculturation style and psychological functioning in children of immigrants. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 66, 111–121. doi: 10.1037/h0080161

Penninx, R., and Garcés-Mascareñas, B. (eds.) (2016). “The Concept of Integration as an Analytical Tool and as a Policy Concept” in Integration Processes and Policies in Europe IMISCOE Research Series. (Springer: Cham), 11–29.

Pollock, G., Ozan, J., and Gowami, H. (2018). “Notions of well-being, the state of child well-being research and the MYWeB Project” in Measuring youth well-being: how a pan-European longitudinal survey can improve policy. eds. G. Pollock, J. Ozan, H. Goswami, G. Rees, and A. Stasulane (Springer International Publishing), 1–15.

Portera, A. (2008). Intercultural education in Europe: epistemological and semantic aspects. Intercult. Educ. 19:6. doi: 10.1080/14675980802568277

Pottie, K., Dahal, G., Georgiads, K., Premji, K., and Hassa, G. (2015). Do first generation immigrant adolescents face higher rates of bullying, violence and suicidal behaviours than do third generation and native born? J. Immigr. Minor. Health 17, 1557–1566. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0108-6

Prince-Embury, S. (2012). “Translating resilience theory for assessment and application with children, Adolescents, and adults: Conceptual issues” in Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults: translating research into practice. eds. S. Prince-Embury and D. H. Sacklofske (Berlin: Springer), 9–16.

Quin, D. (2016). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher-student relationships and student engagement: a systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 87:2. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669434

Reese, G., Bradshaw, J., Goswami, H., and Keung, H. (2010). Understanding Children’s well-being: a National Survey of young People’s well-being. London: The Children’s Society.

Rojas, D. M., Henríquez, W. M., and Rojas, C. M. (2021). Racism, interculturality, and public policies: an analysis of the literature on migration and the school system in Chile, Argentina, and Spain. SAGE Open 11:1. doi: 10.1177/2158244020988526

Rutar, S. (2018). Kakovost šole s perspektive učencev s priseljensko izkušnjo kot izhodišče za zagotavljanje inkluzivnega izobraževanja. [school quality from the perspective of learners with a migrant background as a starting point for inclusive education]. Dve domovini/Two Homelands. 48:2018. doi: 10.3986/dd.v0i48.7131

Rytter, M. (2019). Writing against integration: Danish imaginaries of culture, race, and belonging. Ethnos 84:4. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2018.1458745

Säävälä, M. (2012). The burden of difference? School welfare personnel's and parents' views on well-being of migrant children in Finladn. Finnish Yearb. Popul. Res. 47:2012. doi: 10.23979/fypr.45073

Samdal, O., Nutbeam, D., Wold, B., and Kannas, L. (1998). Achieving health and educational goals through schools – a study of the importance of the school climate and the students’ satisfaction with school. Health Educ. Res. 13:3. doi: 10.1093/her/13.3.383

Schinkel, W. (2018). Against immigrant integration: for an end to neocolonial knowledge production. Comp. Migr. Stud. 6:1. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0095-1

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., and Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 65:4. doi: 10.1037/a0019330

Şeker, B. D., and Sirkeci, I. (2015). Challenges for refugee children at school in eastern Turkey. Econ. Soc. 8:4. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-4/9

Shoshami, A., Nakash, O., Zubida, H., and Harper, R. (2016). School engagement, acculturation, and mental health among migrant adolescents in Israel. Sch. Psychol. Q. 31:2. doi: 10.1037/spq0000133

Sirin, S. R., and Rogers-Sirin, L. (2015). The education and mental health needs of Syrian refugee children. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Smith, M., Spencer, G., Fouché, C., and Hoare, K. (2021). Understanding child and youth migrant well-being: reflections from a systematic literature review in the Western Pacific region. Well-being Space Soc. 2:2021. doi: 10.1016/j.wss.2021.100053

The Children’s Society (2010). Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/Understanding.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2022).

Torres, C. A., and Tarozzi, M. (2019). Multiculturalism in the world system: towards a social justice model of inter/multicultural education. Glob. Soc. Educ. 18:1. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2019.1690729

Trentacosta, C. J., McLear, C. M., Ziadni, M. S., Lumley, M. A., and Arfken, C. L. (2016). Potentially traumatic events and mental health problems among children of Iraqi refugees: the roles of relationships with parents and feelings about school. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 86:4. doi: 10.1037/ort0000186

Viner, R. M., Ozer, M. E., Denny, S., Marmot, M., Resnick, M., Fatusi, A., et al. (2021). Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 379:9826. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4

Vižintin, M. A., and Kern, B. (2022). Začetni tečaj slovenščine in medkulturni dialog pri vključevanju otrok priseljencev. [Beginner course in Slovenan and intercultural dialogue for the integration of migrant children]. Dve domovini/Two Homelands. 56:2022. doi: 10.3986/dd.2022.2.10

Wang, M. T., and Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: a review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 315–352. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

Wang, M. T., Degol, J. L., Amemiya, J., Parr, A., and Guo, J. (2020). Classroom climate and children’s academic and psychological well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 57:100912. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2020.100912

Weissberg, R. P., and O’Brien, M. U. (2004). What works in school-based social and emotional learning programs for positive youth development. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 591:1. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260093

Wong, C. W. S., and Schweitzer, R. D. (2017). Individual, premigration and postsettlement factors, and academic achievement in adolescents from refugee backgrounds: a systematic review and model. Transcult. Psychiatry 54, 5–6. doi: 10.1177/1363461517737015

World Health Organization (2012). Measurement of and target-setting for well-being: An initiative by the WHO regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/180048/E96732.pdf (Accessed September 30, 2022).

World Health Organization (2018). Adolescent health. Available at: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (Accessed July 20, 2022).

Keywords: migrant adolescents, school, school well-being, educational system, intercultural education, migrations, multiculturalism

Citation: Dežan L and Sedmak M (2023) How do you feel at school? A cross-country comparative analysis of migrant adolescents’ school well-being. Front. Educ. 8:1003762. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1003762

Edited by:

Sara Victoria Carrasco Segovia, University of Barcelona, SpainCopyright © 2023 Dežan and Sedmak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucija Dežan,  lucija.dezan@zrs-kp.si

lucija.dezan@zrs-kp.si

Lucija Dežan

Lucija Dežan Mateja Sedmak

Mateja Sedmak